Let me ask you something. What makes up an operating system (OS)? Really think about this for a second and consider what it is about Android, Chrome OS, Windows, or iOS that make any of them your OS of choice.

Let me ask you something. What makes up an operating system (OS)? Really think about this for a second and consider what it is about Android, Chrome OS, Windows, or iOS that make any of them your OS of choice.

What makes each one unique?

Now, let’s bring that consideration into a more narrow funnel. When considering an OS for a tablet, laptop or phone, which do you prefer: Android or Chrome OS?

Since both Android and Chrome OS’ inception, they have lived as unique systems under Google’s roof. Android is the phone and tablet OS. Chrome is the desktop and laptop OS. Android offers a superior app selection. Chrome offers a superior desktop browsing experience. Android makes great use of touch input. Chrome OS takes best advantage of web services and progressive web apps.

They have been siloed, with users of each OS pining for the features the other offered.

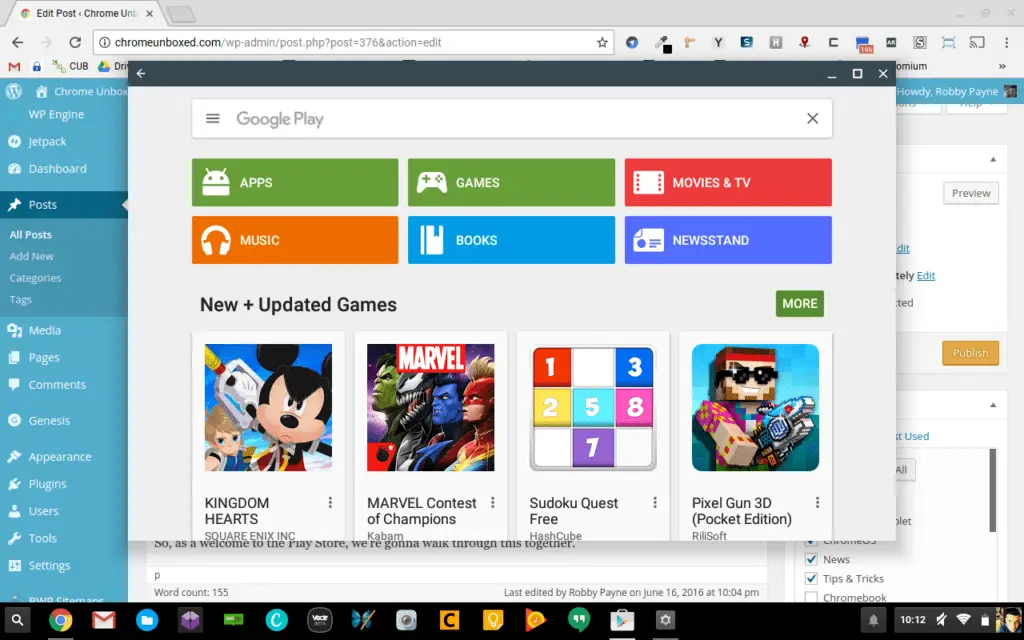

But all that is about to change dramatically with the arrival of the Play Store on Chrome OS in the coming days. And that change summons a very interesting question, indeed.

What is an OS, really?

I’m not about to get all technical and break down API’s, kernels, and architectures that are the fundamental building blocks of operating systems. I don’t have the technical knowledge to do that even if I wanted to. Instead, I want to look at this from the general user’s point of view.

For most people, the OS on any device is simply a launchpad for applications. Since 2007, when Apple’s iPhone hit the scene, our computing use has been forever altered. With apps becoming a mainstream ideology within a few years of its launch, the iPhone and subsequent iOS changed the way we consider our computing devices.

The days of being chained to a specific set of programs that came bundled with a computer began to melt away. High-priced software bought in a store slowly began to be replaced with low cost, low-overhead apps that were able to be purchased right on the device itself. Instead of bloated software suites, we had the ability to find and install a simple app that could take care of the job at hand and that job only.

It was a revolution made at a time (seemingly long ago) when Apple was still pretty revolutionary. (Sorry Apple folks, I couldn’t help it!)

As we move into today’s usage patterns, what we see are app stores being offered for every major OS. Android, iOS, Windows, MacOS and even Chrome OS all have their versions of an app store. A central place to download and purchase tiny applications that do really cool stuff on your device. We all know about them, we all use them, and we mostly love them.

A few years ago, Google made a very interesting move as they created Google Play Services. The short version is Google needed a way to keep all the parts of Android up to date even when OEM’s like Samsung and HTC were slow at updating Android itself.

Things like the phone, camera, calculator, clock, calendar, etc. at one time were all part of the actual OS itself. To get that new camera, you were stuck waiting for your phone manufacturer to get Android updated so you could see the new services on your phone.

This is not the case any longer. Google has, effectively, taken all the user-facing bits of what we know to be Android and separated them from Android itself. This is why you see super-cheap tablets on Amazon that may or may not contain the Play Store. No Play Store means no official Google apps. Which means your phone won’t do much without the manufacturer having some software tweaks done. Or, as in the case of Amazon’s Kindle tablets, a full-blown OS skin on top of Android.

There’s more to that story, but I simply want to make this point: the Android you see on a Nexus device (what some call ‘vanilla’) is vastly different than the Android a manufacturer sees when they install AOSP (Android Open Source Project). It is different and vastly inferior because Android without all the little apps that make up the UI doesn’t really feel like Android at all.

An example of this, shall we? When I pull my phone out of my pocket, I unlock it. I navigate my home screens in a launcher. I launch a few social network apps, a calendar, and a browser. I check my notifications. And finally I go into my settings to check and see if my Nougat update has arrived yet.

Of all those actions, only two of them are functions of the OS itself. Notifications and settings. However, most OEMs replace both of these parts of Android with regularity. Though Samsung has recently made its notifications pane a bit more like stock Android, it is still custom. And this is fine, honestly. Because of what companies like Samsung and LG have done with the UI bits, we have Android notifications and quick setting in 7.0 that are awesome and borrow from multiple companies’ contributions over the years.

The point, then, is that until you get into settings and under-the-hood stuff, the OS isn’t even really visible.

So, as Android apps begin showing up on Chrome OS devices, the lines are going to get really blurry. Chrome OS notifications and the new material design settings all feel pretty familiar to those who have used their Android counterparts. Finding, installing, and lauching apps is quite similar to the Android experience now for Chromebooks that have the Play Store already. Sure there are some kinks to work out, but the experience feels a lot like using those apps on an Android device, not a Chrome OS device.

Further blurring the lines will be Android 7.0’s ability to run side-by-side and windowed apps. The latter looks a lot like Chrome OS in practice. Or maybe Chrome OS running Android apps looks like Nougat.

See what I mean?

To bring all this home, imagine a scenario. It’s 6 months down the road and you have a 10-inch tablet in your hands. You click the wake/power button and are met with a lockscreen. You unlock the device with your fingerprint. You then use a homescreen launcher to swipe through your widgets and select an app to use. You see a notification pop up and click it, taking you to the app you need. You then recall that you were in the middle of something before that and click the multitask button to see cards of your open apps and select that app. You complete the task and set the tablet down.

Were you on an Android tablet or a Chrome OS tablet? How do you know (assuming launchers become a thing for Chrome OS tablets)? And, more importantly, does it really matter?

And there we have the point of all this. Robbed of the apps you download, the homescreens you use, and the basic functional apps you expect out of the box, what part of the OS, from a daily usage standpoint, really makes Android different from Chrome OS?

In the end, it all comes down to apps. For nearly all users, if you can get all the apps and you need from a given platform, that is all that really matters. The one real differentiator is the desktop experience that Chrome OS offers. Having a full web browsing experience changes things pretty dramatically.

But, again, the Chrome Browser is installable on Windows and MacOS, yet it’s basically the same across all platforms. It’s an extensive app, but it really is just another app. And Chrome OS obviously handles the Chrome browsing experience better than any of them.

This is why we talk about the impact of Android Apps on Chrome OS so much around here. It is a fundamental game-changing move by Google. What would have been ludicrous to consider only months ago is now at least feasible: Google Pixel Phones. While I don’t think these phones will run Chrome OS this time around, I see the implications and the writing on the wall. As the case has been made above, would most people even know the difference or care if their phone was running Chrome OS if the apps were all there and working as expected?

I don’t think so, honestly.

And, Pixel phones are just part of what is possible moving forward. Tablets and Chromebooks with convertible form factors will change the way we consider computing in general, making me wonder if we’ll see a future without Android tablets at all. Who knows?

Though Android apps have a way to go before the user experience on Chromebooks becomes as good as Android, the path is clear and the future is very bright. And the possibilites are seemingly endless.

[Yoga Book Image Credit: computerhoy.com]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.